The Alignment Problem

Why we need to look beyond technical solutions to AI Safety

Datum Ethics Review is a fortnightly (bi-weekly) survey of the latest news and developments in the ethical and social implications of artificial intelligence.

Against the background of the recent crisis in governance at OpenAI (see the previous newsletter if you’ve missed this), researchers from the company’s ‘superalignment team’ have released the results of an experiment designed to test the effectiveness of a new method of supervising advanced AI. Superalignment is intended to address the problem of alignment (or how to ensure AI does what we want it to and nothing more) when AI becomes ‘superintelligent’ (i.e., when AI doesn’t only match but far surpasses our cognitive capacities). While the prospect of AI superintelligence is not universally accepted (see for example Melanie Mitchell’s ‘Why AI is Harder Than We Think’), its inevitability is a given at OpenAI, which was established on the pledge to build AI that benefits all of humanity even when (or if) that intelligence eclipses that of its maker.

The alignment problem is by no means confined to concerns about superintelligence. The influential North American mathematician and computer scientist Norbert Weiner recognised the alignment problem over 60 years ago in his article ‘Some Moral and Technical Consequences of Automation’:

If we use, to achieve our purposes, a mechanical agency with whose operation we cannot efficiently interfere once we have started it, because the action is so fast and irrevocable that we have not the data to intervene before the action is complete, then we had better be quite sure that the purpose put into the machine is the purpose which we really desire and not merely a colorful imitation of it (p. 16).

Contemporary computer scientist Stuart Russell has referred to the same concern as the ‘King Midas problem’: i.e., the optimisation of a specific objective or set of objectives will likely generate exactly what you asked for rather than what you intended. Consider the effects of recommender systems in social media platforms such as Facebook and YouTube. By optimising for user engagement, these systems have inadvertently (though not unknowingly) promoted toxic online cultures in which extreme views and disinformation has proliferated to the detriment of public civility and the quality of public discourse.

As Weiner also noted in his book, God & Golem, Inc. (1966), the fundamental problem is not only that our instructions are all too often imprecise and incomplete, but that we’re ultimately uncertain and/or disagree about what our preferences, intentions, and purposes actually are:

In the past, a partial and inadequate view of human purpose has been relatively innocuous only because it has been accompanied by technical limitations that made it difficult for us to perform operations involving a careful evaluation of human purpose. This is only one of the many places where human impotence has shielded us from the full destructive impact of human folly (p. 64).

The challenge presented by the alignment problem is therefore how to identify appropriate preferences, values, and purposes, and how to then specify objective functions based on these that avoid inappropriate outputs and unintended consequences. This is no easy task given the moral significance and complexity of distinctions between transient preferences, deeply-held commitments, and social, ethical, and legal norms, as well as the nuances of when and how these apply in different circumstances.

In the context of large language models (LLMs), the alignment method of reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) has been central to the popularity of conversational agents such as ChatGPT and Bard (see this explanation of RLHF from Hugging Face). By fine-tuning large language models on the basis of human feedback (e.g., ratings of different outputs, selecting preferred responses to prompts, or correcting undesirable outputs), it’s been possible to release chatbots that are both more engaging and safer insofar as they largely avoid parroting and amplifying offensive views and rhetoric from a model’s training data. As a point of contrast, you may recall the ill-fated release of the Microsoft chatbot Tay on Twitter in 2016. Described as an experiment in conversational understanding, Tay was designed to engage people in casual dialogue, but was soon corrupted by a barrage of racist, misogynist, and otherwise abusive tweets. Microsoft withdrew Tay within 24 hours of its release after it started repeating the same sentiments in its own tweets.

As Narayan et al. (2023) have noted, RLHF has been effective at preventing accidental harms to average users but is not a safeguard against intentional harms, whether from average users who occasionally do harmful things or malicious actors with relevant expertise and resources. Examples include jailbreak prompts that bypass a model’s safeguards in order to generate hate speech and disinformation, and prompt injections designed to coax the system into performing unauthorised actions such as manipulating an LLM-driven email spam filter to steal personal data. If we take seriously the prospect of artificial superintelligence, it’s clear that vastly more robust and comprehensive methods of alignment will be needed.

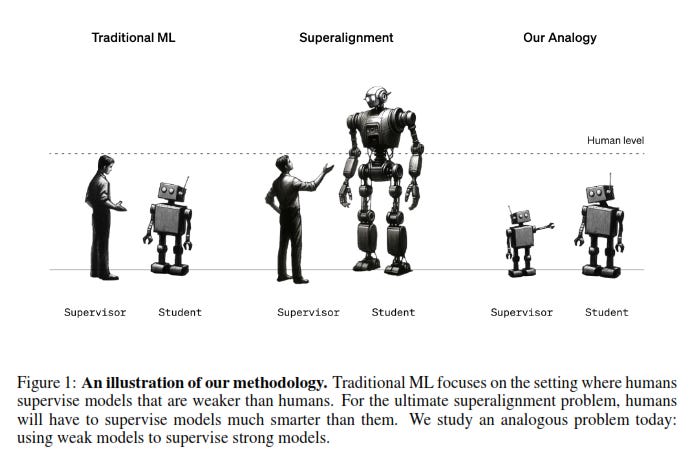

The problem addressed by OpenAI’s superalignment team presumes that humans will be unable to reliably evaluate the performance of AI systems that surpass their own cognitive capacities for two reasons: human supervisors may not understand the output of superintelligent systems and so would be unable to appropriately evaluate it, while such systems may produce deceptive outputs in order to undermine any attempt at supervision. Researchers were therefore interested in how effective the weak supervision that human feedback would be able to provide in these circumstances (referred to as ‘weak-to-strong learning’) would be. In the absence of superintelligent systems, researchers studied an analogous problem – whether a relatively weak model such as GPT-2 could be used to fine-tune a stronger model such as GPT-4. (The figure below was taken from page 2 of the article).

Among the findings of the study were that the straightforward (or naïve) application of RLHF is likely to scale poorly to superintelligent models without additional work, but that when stronger models are supervised by weaker ones the resulting loss of performance (the weak-to-strong generalisation) can be limited to 20% of the performance gap between weak and strong models. Despite the acknowledged limitations of the study, researchers were optimistic that they had at least developed a way of studying the problem of superalignment empirically:

With much progress in this direction, we could get to the point where we can use weak supervisors to reliably elicit knowledge from much stronger models, at least for some key tasks that we care about. This may allow us to develop superhuman reward models or safety classifiers, which we could in turn use to align superhuman models.

Nonetheless, given the limitations of RLHF mentioned above, if the effectiveness of existing alignment methods such as RLHF are viewed as an appropriate benchmark for future developments, we can be forgiven for being more pessimistic than the superalignment team at OpenAI.

What gets overlooked when treating AI alignment as a solely technical problem is that the socio-cultural contexts in which technologies such as AI are deployed are not well-ordered systems with clear or at least empirically discoverable laws of cause and effect. They are instead complex and messy networks of relations that include human agents such as engineers, investors, users, regulators, and activists, as well as social institutions, material infrastructure, resource availability, supply chains, and impacts on the natural environment. And as Helen Nissenbaum reminds us, “we cannot simply align the world with the values and principles we adhered to prior to the advent of technological challenges” (p. 118).

A more realistic, socio-technical approach to AI alignment includes (among many other things) a willingness to consider multiple accounts of what AI is or could be, as well as the manifold values, norms, purposes, and practices that it will need to be attuned to and co-ordinated with.

In this vein, it’s worth considering Jaron Lanier’s provocation that there is no such thing as AI insofar as it’s regarded as a hypothetical creature or mind rather than a tool:

Mythologizing the technology only makes it more likely that we’ll fail to operate it well—and this kind of thinking limits our imaginations, tying them to yesterday’s dreams. We can work better under the assumption that there is no such thing as A.I. (para. 5).

Lanier encourages us instead to regard AI as an innovative form of social collaboration, with generative AI (for example) understood as a mashup of human creativity that reveals previously unrecognised concordances between the artefacts of human intelligence.

Seeing A.I. as a way of working together, rather than as a technology for creating independent, intelligent beings, may make it less mysterious—less like HAL 9000 [from the film 2001: A Space Odyssey] or Commander Data [from the Star Trek TV series and films]. But that’s good, because mystery only makes mismanagement more likely (para. 8).

In this sense, AI could be a means of making more transparent the connections between humans as well as humans and machines, rather than something for which transparency is an ongoing concern. This of course would not prevent the misuse of AI, as the dual-use nature of most (if not all) artefacts (even the humble fork, but most obviously technologies such as nuclear energy and synthetic biology) means that how they’re used is the subject of norms, regulations, and sanctions. But it does place the responsibility for how AI is used as a tool squarely back on us, which is where I believe it belongs.

From elsewhere …

If you’re interested in reading more about the alignment problem, Brian Christian’s book of the same name is a good place to start.

Since the last edition of Datum Ethics Review was published, the EU AI Act moved a step closer to becoming law after long and intense negotiations between the European Council presidency and the European Parliament’s negotiators. Provisional agreement was reached on outstanding issues such as how to regulate foundation models and whether open-source models should be treated in the same way as closed models (see this summary of what we know of the agreed text from Osborne Clarke). If you want to know more, visit this website from Accessible Law that includes the text of the act along with updates and a blog.

On the topic of open-source AI, this issue brief on the governance of open foundation models from Bommasani et al. (2023) provides a clear overview of the regulatory approaches currently being considered.

Here’s an update on the US Executive Order (EO) on Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence from Will Knight at WIRED that discusses concerns about the lack of resources at National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), which has a key role in the implementation of the EO: ‘America’s Big AI Safety Plan Faces a Budget Crunch’

This episode of the Me, Myself, and AI podcast (2023, December 19) - ‘AI on Mars: NASA’s Vandi Verma’ (Episode 806) - discusses the use of AI by NASA in its Mars rovers with Vandi Verma, Chief Engineer for Robotic Operations for the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover. What I found particularly interesting was the discussion of NASA’s approach to the use of digital simulations and its management of the risks involved in automated decisions and processes.

Given the importance of the elections to be held in 2024, you’re probably at least as familiar as I am with concerns over the role of AI generated messages, images, and videos flooding online platforms with mis- and dis-information. As a corrective, I recommend reading this article from Simon et al. (2023), which argues that these concerns are exaggerated - ‘Misinformation reloaded? Fears about the impact of generative AI on misinformation are overblown’ (Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review, vol. 4, issue 5).

I also recommend this article from Jack Stilgoe on the basis of trust in new technologies such as self-driving vehicles - ‘What does it mean to trust a technology?’ (Science, vol. 382, issue 6676).

The next edition of Datum Ethics Review will be posted in mid-January, so until then I wish you well no matter where you are or what you’re celebrating or suffering through.